This post originally published on the Museum Victoria blog to welcome the "Art of Science" exhibit to the museum and introduce audiences to BHL. Explore the latest BHL Australia developments in this past post. See the Museum Victoria collection in BHL here.

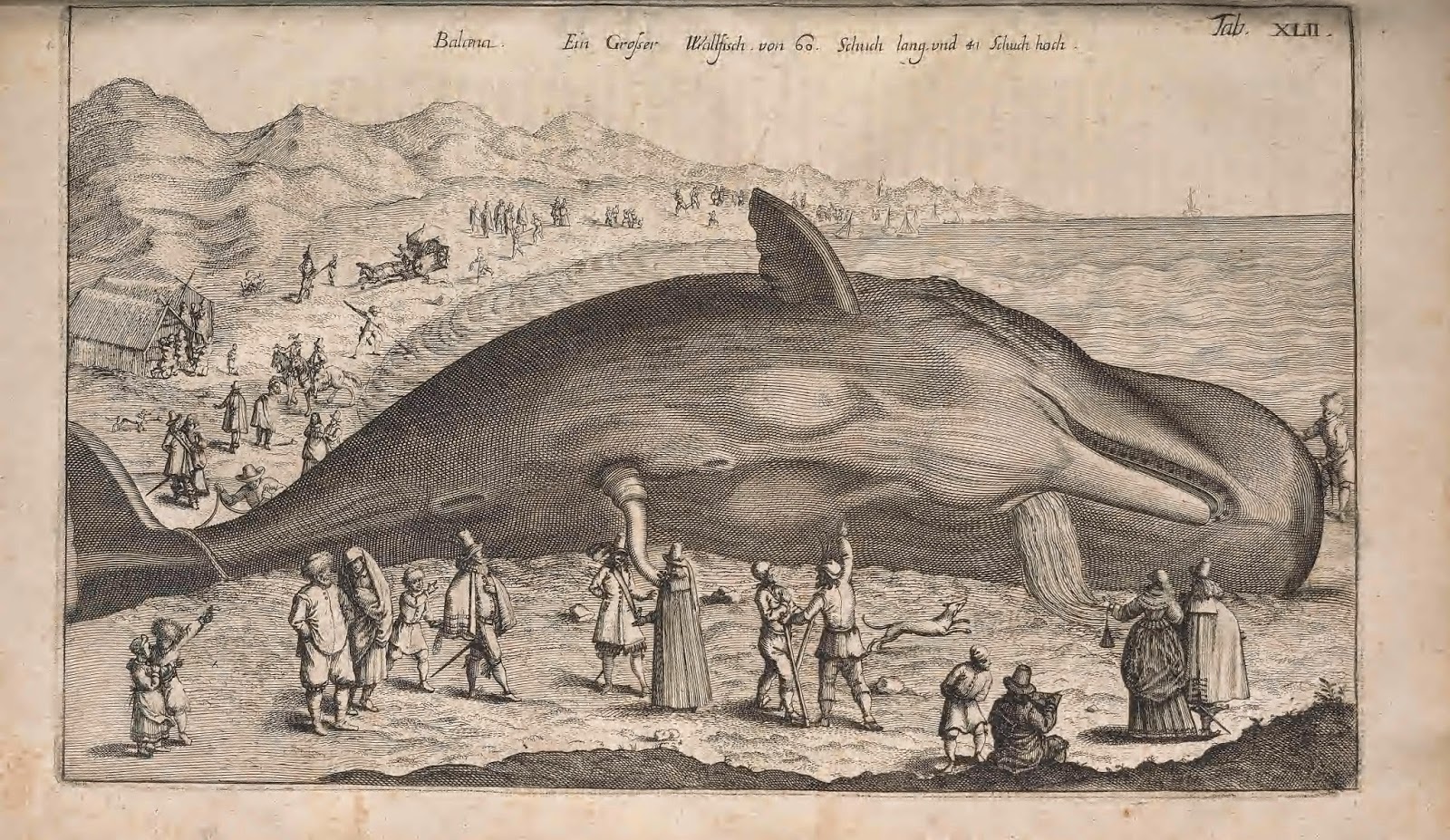

The Art of Science exhibition presents the finest examples from Museum Victoria's remarkable collection of natural history artworks. These include rare books from the 18th and 19th centuries, field sketches from early colonial exploration of Australia's wildlife, and contemporary scientific photographs.

The books on display contain some of the most beautiful and significant illustrations of flora and fauna ever produced. The exhibition's curators must have had a torturous task selecting which page from each book to display. Because that's all they could display – a single double page spread from each precious volume.

The Art of Science has only just opened at the Melbourne Museum. Before coming home, it toured Mornington, Ballarat, Adelaide, Mildura, Sale and Sydney. Visitors to the traveling exhibition were awed by the stunning illustrations, but they were also a little frustrated. They wanted to turn those beautiful pages. They wanted to see more.

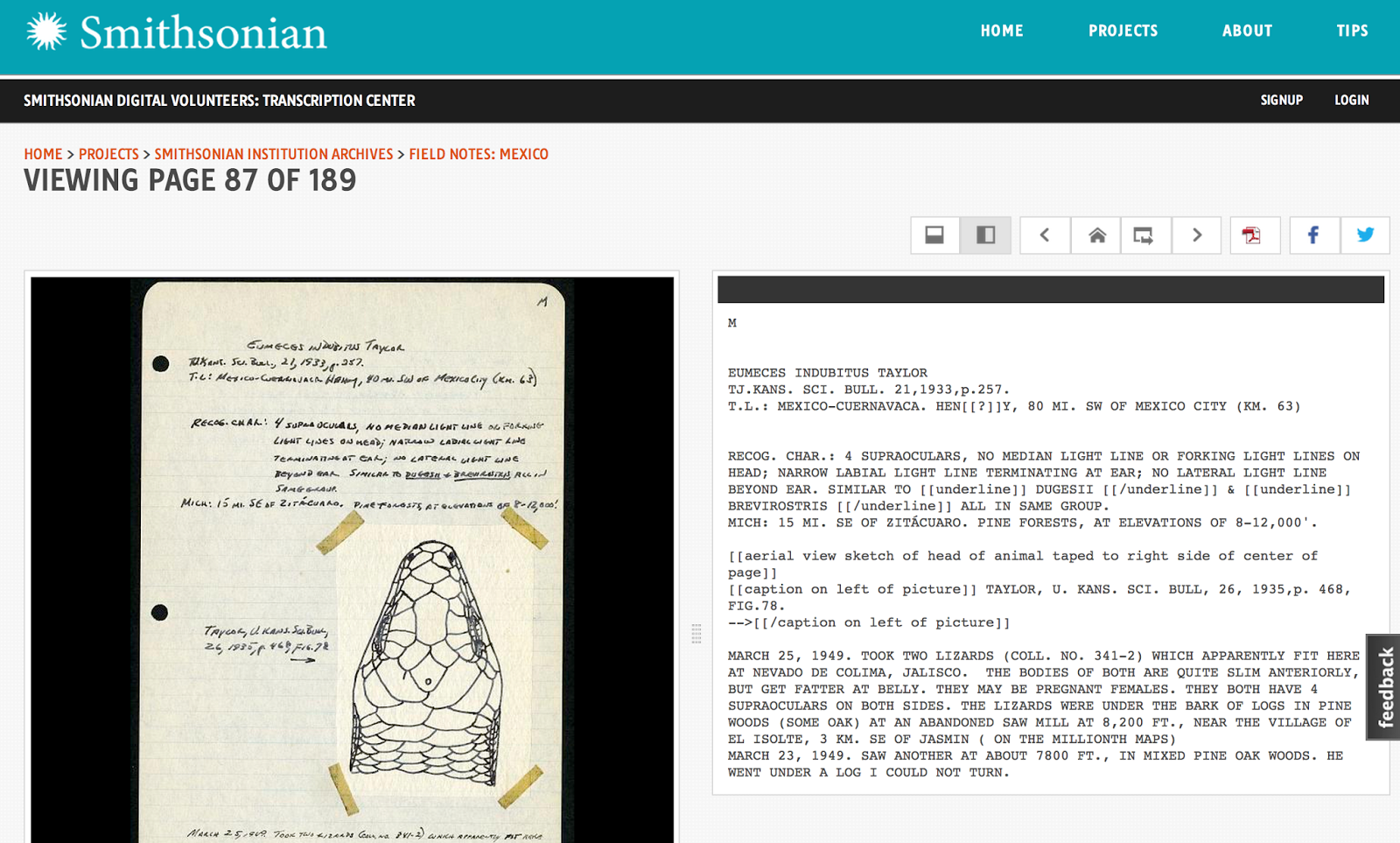

And so, before the books went on display for this final time, we asked the exhibition's curators if we could borrow them. Each page of every book was carefully photographed and the images color matched to the originals. This work was meticulously performed by a group of dedicated museum volunteers, supervised by Museum Victoria's library staff.

We then uploaded the scanned volumes into the world's largest online repository of biodiversity literature and archival materials – the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL). BHL is a global consortium of natural history libraries working together to make biodiversity literature freely and openly available to everyone.

Museum Victoria coordinates the Australian component of this giant online library, and we are thrilled that the books displayed in The Art of Science exhibition are now part of it.

So if you too would like to turn those tantalizing pages, now you can (whether you're in Melbourne, or not):

The Art of Science exhibition presents the finest examples from Museum Victoria's remarkable collection of natural history artworks. These include rare books from the 18th and 19th centuries, field sketches from early colonial exploration of Australia's wildlife, and contemporary scientific photographs.

The books on display contain some of the most beautiful and significant illustrations of flora and fauna ever produced. The exhibition's curators must have had a torturous task selecting which page from each book to display. Because that's all they could display – a single double page spread from each precious volume.

|

| Major Mitchell's Cockatoo, illustrated by Elizabeth Gould for John Gould's A synopsis of the birds of Australia, and the adjacent islands, 1st edition, London, 1837-38, on display at Melbourne Museum. The entire book can now be viewed online. Image: Nicole Kearney Source: Museum Victoria |

The Art of Science has only just opened at the Melbourne Museum. Before coming home, it toured Mornington, Ballarat, Adelaide, Mildura, Sale and Sydney. Visitors to the traveling exhibition were awed by the stunning illustrations, but they were also a little frustrated. They wanted to turn those beautiful pages. They wanted to see more.

|

| Wombat, from An account of the English colony in New South Wales, from its first settlement in January 1788 to August 1801, David Collins, 1804. The entire book can now be viewed online. Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library |

And so, before the books went on display for this final time, we asked the exhibition's curators if we could borrow them. Each page of every book was carefully photographed and the images color matched to the originals. This work was meticulously performed by a group of dedicated museum volunteers, supervised by Museum Victoria's library staff.

|

| Ground Parrot, illustrated by James Sowerby, for George Shaw's Zoology of New Holland, volume 1, 1st edition, London, 1794. The entire book can now be viewed online. Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library |

We then uploaded the scanned volumes into the world's largest online repository of biodiversity literature and archival materials – the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL). BHL is a global consortium of natural history libraries working together to make biodiversity literature freely and openly available to everyone.

Museum Victoria coordinates the Australian component of this giant online library, and we are thrilled that the books displayed in The Art of Science exhibition are now part of it.

So if you too would like to turn those tantalizing pages, now you can (whether you're in Melbourne, or not):

- Visit the BHL website to view The Art of Science books in their entirety.

- Visit The Art of Science exhibition at Melbourne Museum to view a selection of the scanned pages on an interactive screen.

Nicole Kearney

BHL Australia Project Coordinator

BHL Australia Project Coordinator

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)